Healing Country with cultural fire

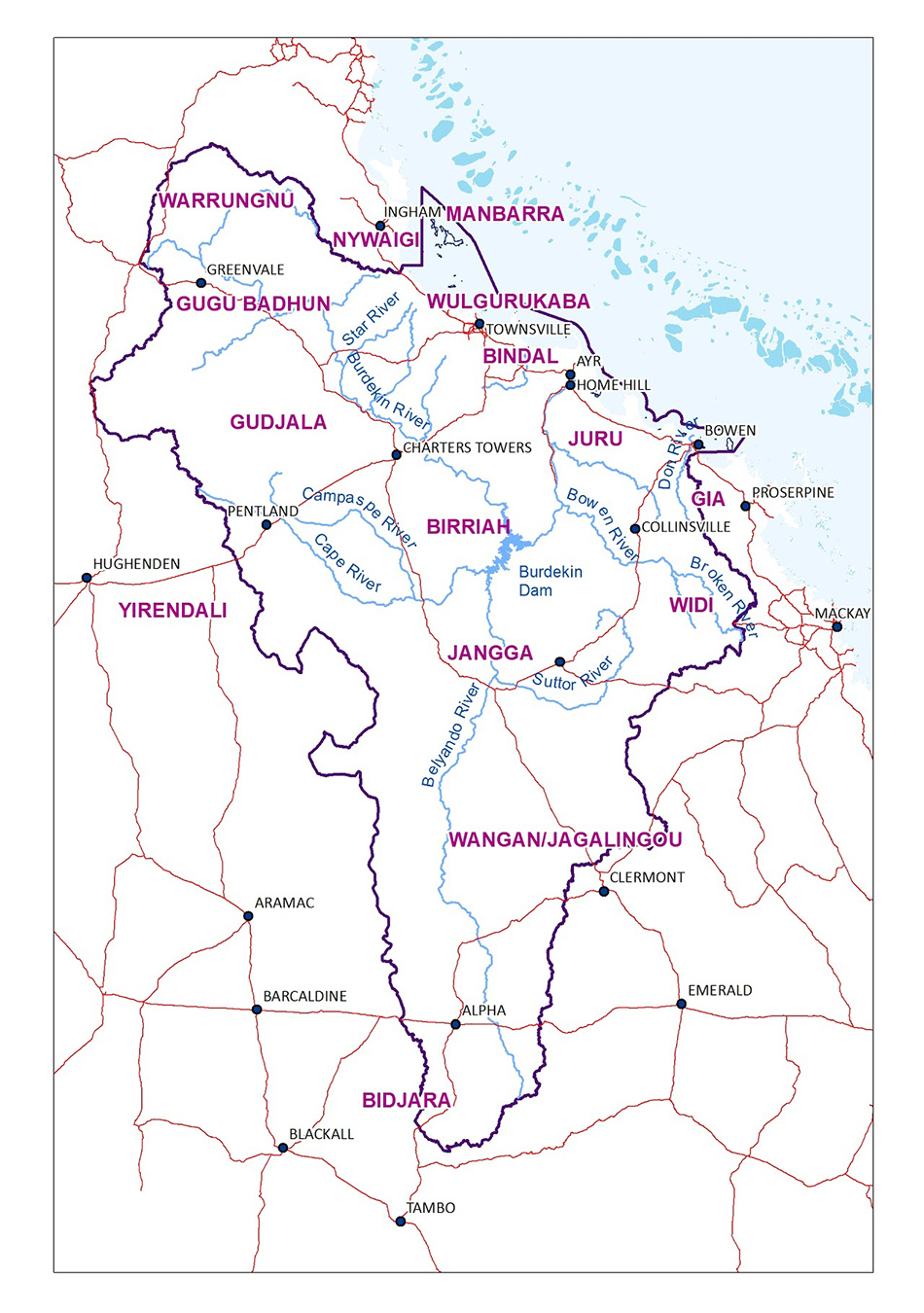

The Burdekin Dry Tropics Traditional Owner Management Group (TOMG), which consists of leaders from 14 Traditional Owner groups, has been providing advice and direction to NQ Dry Tropics for more than 20 years.

In 2020 the TOMG identified a priority to build regional First Nations people’s capacity and capability to undertake cultural fire practices. As a result, NQ Dry Tropics worked closely with the TOMG to develop and design the Cultural Fire Management for Grazing Landscapes project.

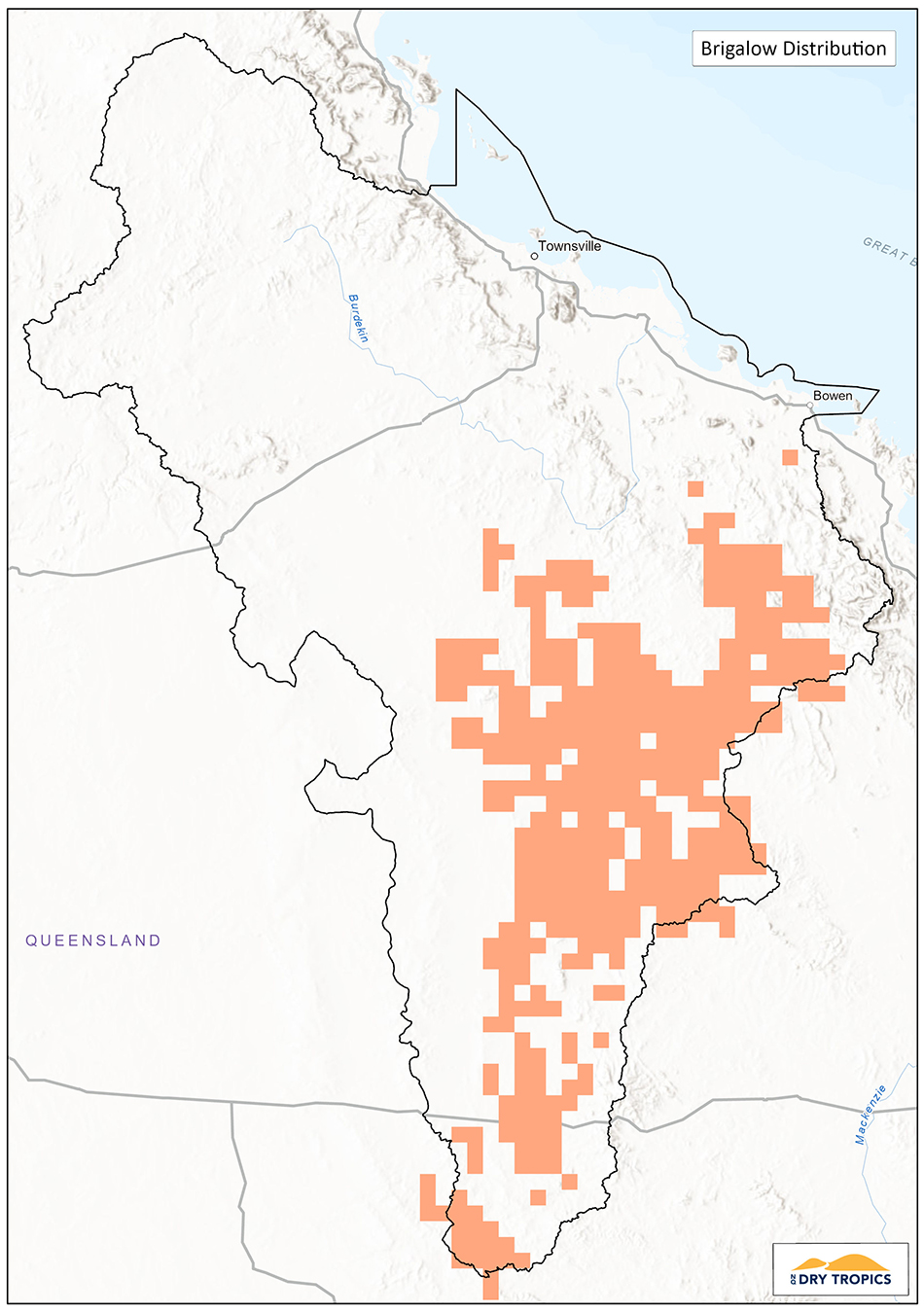

Delivered in partnership between Traditional Owners of the Burdekin Dry Tropics region, WWF-Australia, Firesticks Alliance, and graziers, the project’s main objective is to revitalise ancient cultural fire management practices among Traditional Owners, while strengthening their relationships with graziers as they work together to heal Country. The project, which employs a full time First Nations Cultural Fire Management Project Officer, aims to demonstrate how cultural fire can improve the health and productivity of grazing land, benefit biodiversity, and greatly reduce the risk of wildfires.

Organic cattle property Jervoise Station, on Gugu Badhun country near Greenvale, is operated by three generations of the Jonsson family. They were keen to get involved, and were chosen as a demonstration site for a carefully-planned two-year cultural fire management regime overseen by Gugu Badhun Traditional Owners and Firesticks Alliance Lead Fire Practitioner, Victor Steffensen.

Mr Steffensen said traditional knowledge and cultural fire management was needed back in the landscape to address environmental problems:

“This is about connecting people back to Country and healing Country in a way that improves landscapes and livelihoods at the same time,” Mr Steffensen said.

During a series of facilitated workshops and burns, Traditional Owners and grazing property owners learned more about reading Country, helping them to better understand landscape condition and determine how to restore balance through cultural burning.

Four workshops have been held so far on Gugu Badhun and Bindal country, all of which were well-attended, with 12 of the regions’ Traditional Owner groups represented from across the region including Traditional Owner Elders, Gudjuda Rangers, Girringun Rangers, Minggamingga Rangers, Wulgurukaba QPWS Rangers, Rural Fire Service, and Indigenous employment group Three Big Rivers.

The “Cultural Fire Management for Grazing Landscapes” project is funded through WWF-Australia’s Indigenous Fire Management Program.

Workshop participants (from left) Reg Kerr (Gudjala), Richard Hoolihan (Gugu Badhun), Scott Crawford (CEO, NQ Dry Tropics), Ben Kitchener (Indigenous Fire Coordinator, WWF-Australia), Victor Steffensen (Firesticks Alliance Lead Fire Practitioner), Jervoise grazier Greg Jonsson with granddaughter Ashton Reynolds, and Josephine Smallwood (Wangan and Jagalingou).

Traditional Owner Management Group

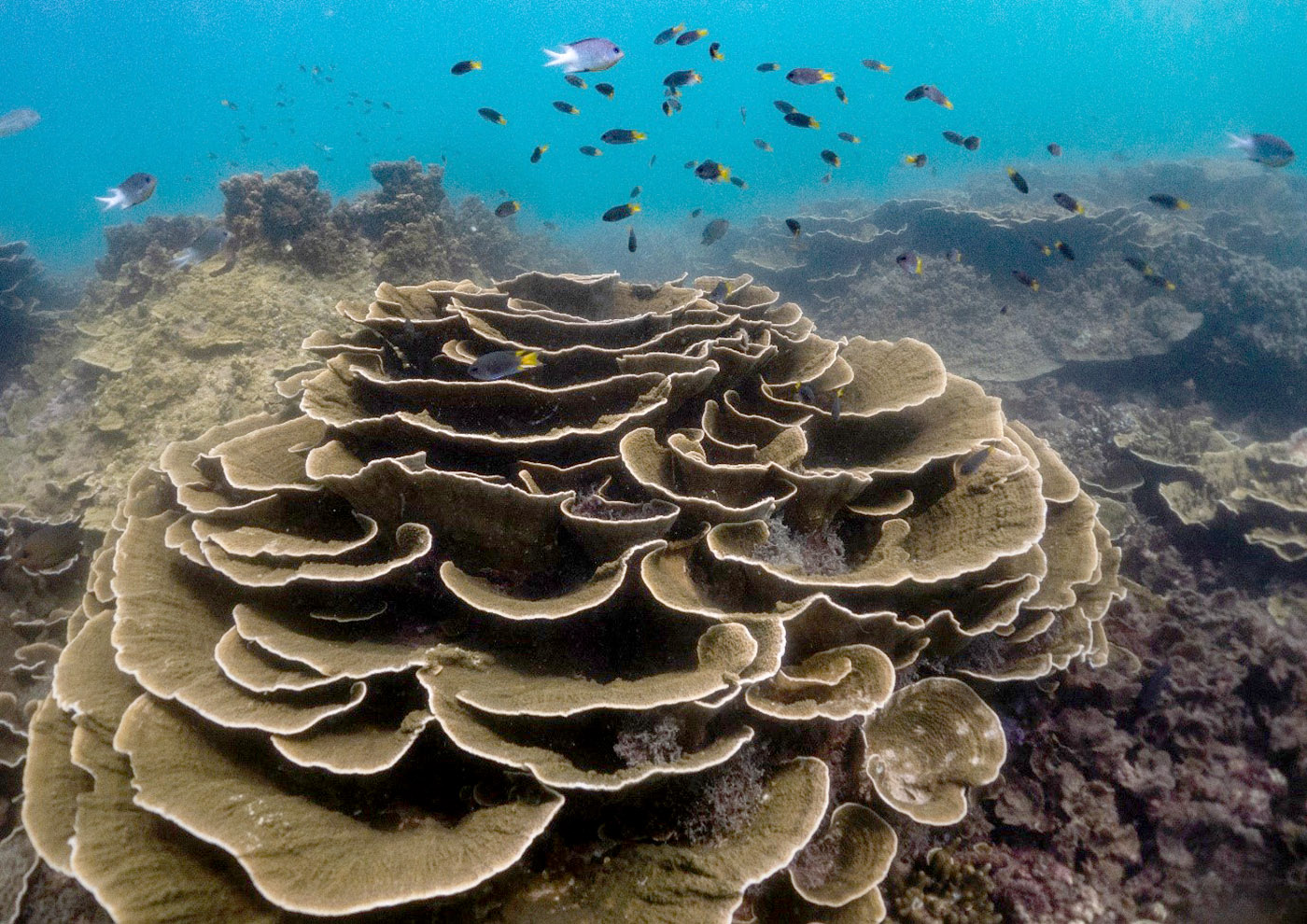

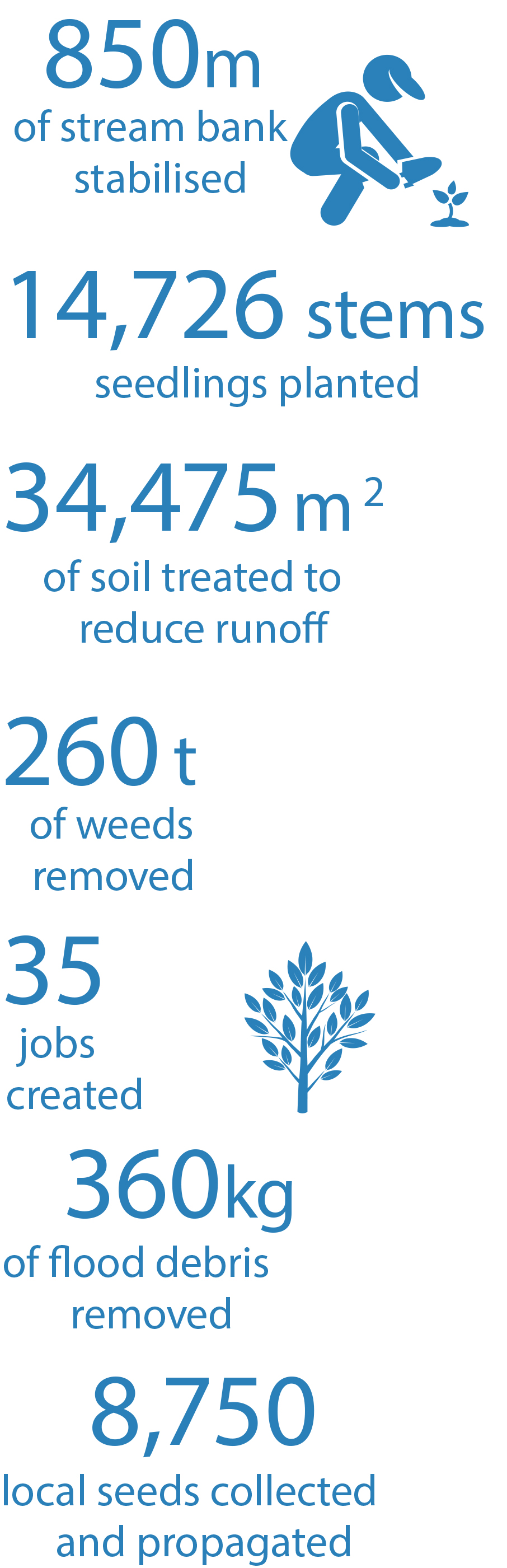

The Townsville City Council’s (TCC) Reef Assist – Business Activity and Environmental Restoration project was funded through the initial stage of the Queensland Government’s $33.5 million Reef Assist program.

The Townsville City Council’s (TCC) Reef Assist – Business Activity and Environmental Restoration project was funded through the initial stage of the Queensland Government’s $33.5 million Reef Assist program. The Reef Assist project has continued throughout 2022, delivering continued beneficial outcomes for local waterways, including the construction of leaky weirs and other sediment erosion control structures, and thousands more local native tree plantings.

The Reef Assist project has continued throughout 2022, delivering continued beneficial outcomes for local waterways, including the construction of leaky weirs and other sediment erosion control structures, and thousands more local native tree plantings.